2.1. Rhythm*

Rhythm, melody, harmony, timbre, and texture are the essential aspects of a musical performance. They are often called the basic elements of music. The main purpose of music theory is to describe various pieces of music in terms of their similarities and differences in these elements, and music is usually grouped into genres based on similarities in all or most elements. It's useful, therefore, to be familiar with the terms commonly used to describe each element. Because harmony is the most highly developed aspect of Western music, music theory tends to focus almost exclusively on melody and harmony. Music does not have to have harmony, however, and some music doesn't even have melody. So perhaps the other three elements can be considered the most basic components of music.

Music cannot happen without time. The placement of the sounds in time is the rhythm of a piece of music. Because music must be heard over a period of time, rhythm is one of the most basic elements of music. In some pieces of music, the rhythm is simply a "placement in time" that cannot be assigned a beat or meter, but most rhythm terms concern more familiar types of music with a steady beat. See Meter for more on how such music is organized, and Duration and Time Signature for more on how to read and write rhythms. See Simple Rhythm Activities for easy ways to encourage children to explore rhythm.

Rhythm Terms

-

Rhythm - The term "rhythm" has more than one meaning. It can mean the basic, repetitive pulse of the music, or a rhythmic pattern that is repeated throughout the music (as in "feel the rhythm"). It can also refer to the pattern in time of a single small group of notes (as in "play this rhythm for me").

-

Beat - Beat also has more than one meaning, but always refers to music with a steady pulse. It may refer to the pulse itself (as in "play this note on beat two of the measure"). On the beat or on the downbeat refer to the moment when the pulse is strongest. Off the beat is in between pulses, and the upbeat is exactly halfway between pulses. Beat may also refer to a specific repetitive rhythmic pattern that maintains the pulse (as in "it has a Latin beat"). Note that once a strong feeling of having a beat is established, it is not necessary for something to happen on every beat; a beat can still be "felt" even if it is not specifically heard.

-

Measure or bar - Beats are grouped into measures or bars. The first beat is usually the strongest, and in most music, most of the bars have the same number of beats. This sets up an underlying pattern in the pulse of the music: for example, strong-weak-strong-weak-strong-weak, or strong-weak-weak-strong-weak-weak. (See Meter.)

-

Rhythm Section - The rhythm section of a band is the group of instruments that usually provide the background rhythm and chords. The rhythm section almost always includes a percussionist (usually on a drum set) and a bass player (usually playing a plucked string bass of some kind). It may also include a piano and/or other keyboard players, more percussionists, and one or more guitar players or other strummed or plucked strings. Vocalists, wind instruments, and bowed strings are usually not part of the rhythm section.

-

Syncopation - Syncopation occurs when a strong note happens either on a weak beat or off the beat. See Syncopation.

1.3. Style

Dynamics and Accents*

Dynamics

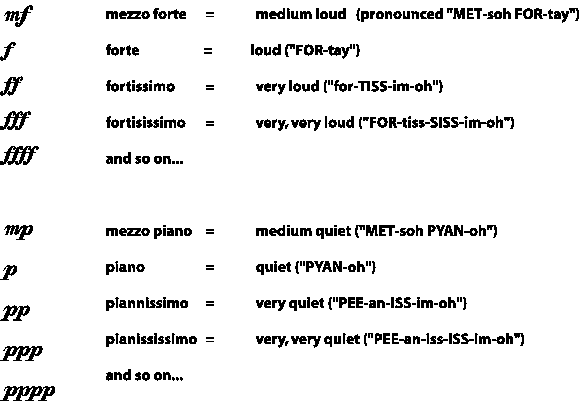

Sounds, including music, can be barely audible, or loud enough to hurt your ears, or anywhere in between. When they want to talk about the loudness of a sound, scientists and engineers talk about amplitude. Musicians talk about dynamics. The amplitude of a sound is a particular number, usually measured in decibels, but dynamics are relative; an orchestra playing fortissimo sounds much louder than a single violin playing fortissimo. The exact interpretation of each dynamic marking in a piece of music depends on:

-

comparison with other dynamics in that piece

-

the typical dynamic range for that instrument or ensemble

-

the abilities of the performer(s)

-

the traditions of the musical genre being performed

-

the acoustics of the performance space

Traditionally, dynamic markings are based on Italian words, although there is nothing wrong with simply writing things like "quietly" or "louder" in the music. Forte means loud and piano means quiet. The instrument commonly called the "piano" by the way, was originally called a "pianoforte" because it could play dynamics, unlike earlier popular keyboard instruments like the harpsichord and spinet.

Figure 1.89. Typical Dynamic Markings

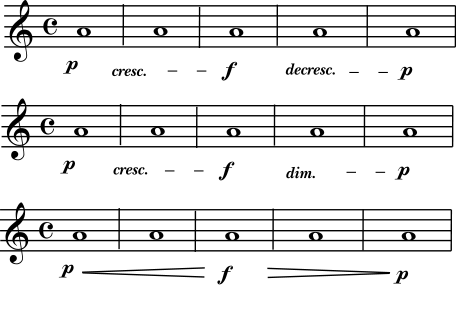

When a composer writes a forte into a part, followed by a piano, the intent is for the music to be loud, and then suddenly quiet. If the composer wants the change from one dynamic level to another to be gradual, different markings are added. A crescendo (pronounced "cresh-EN-doe") means "gradually get louder"; a decrescendo or diminuendo means "gradually get quieter".

Figure 1.90. Gradual Dynamic Markings

Accents

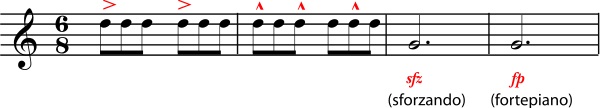

A composer may want a particular note to be louder than all the rest, or may want the very beginning of a note to be loudest. Accents are markings that are used to indicate these especially-strong-sounding notes. There are a few different types of written accents (see Figure 1.91), but, like dynamics, the proper way to perform a given accent also depends on the instrument playing it, as well as the style and period of the music. Some accents may even be played by making the note longer or shorter than the other notes, in addition to, or even instead of being, louder. (See articulation for more about accents.)

Figure 1.91. Common Accents

Articulation*

What is Articulation?

The word articulation generally refers to how the pieces of something are joined together; for example, how bones are connected to make a skeleton or syllables are connected to make a word. Articulation depends on what is happening at the beginning and end of each segment, as well as in between the segments.

In music, the segments are the individual notes of a line in the music. This could be the melodic line, the bass line, or a part of the harmony. The line might be performed by any musician or group of musicians: a singer, for example, or a bassoonist, a violin section, or a trumpet and saxophone together. In any case, it is a string of notes that follow one after the other and that belong together in the music.The articulation is what happens in between the notes. The attack - the beginning of a note - and the amount of space in between the notes are particularly important.

Performing Articulations

Descriptions of how each articulation is done cannot be given here, because they depend too much on the particular instrument that is making the music. In other words, the technique that a violin player uses to slur notes will be completely different from the technique used by a trumpet player, and a pianist and a vocalist will do different things to make a melody sound legato. In fact, the violinist will have some articulations available (such as pizzicato, or "plucked") that a trumpet player will never see.

So if you are wondering how to play slurs on your guitar or staccato on your clarinet, ask your music teacher or director. What you will find here is a short list of the most common articulations: their names, what they look like when notated, and a vague description of how they sound. The descriptions have to be vague, because articulation, besides depending on the instrument, also depends on the style of the music. Exactly how much space there should be between staccato eighth notes, for example, depends on tempo as well as on whether you're playing Rossini or Sousa. To give you some idea of the difference that articulation makes, though, here are audio examples of a violin playing a legato and a staccato passage. (For more audio examples of violin articulations, please see Common Violin Terminology.)

Common Articulations

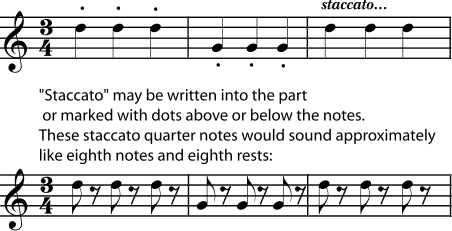

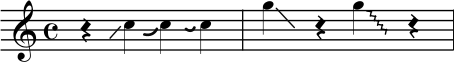

Staccato notes are short, with plenty of space between them. Please note that this doesn't mean that the tempo or rhythm goes any faster. The tempo and rhythm are not affected by articulations; the staccato notes sound shorter than written only because of the extra space between them.

Figure 1.92. Staccato

Legato is the opposite of staccato. The notes are very connected; there is no space between the notes at all. There is, however, still some sort of articulation that causes a slight but definite break between the notes (for example, the violin player's bow changes direction, the guitar player plucks the string again, or the wind player uses the tongue to interrupt the stream of air).

Figure 1.93. Legato

Accents - An accent requires that a note stand out more than the unaccented notes around it. Accents are usually performed by making the accented note, or the beginning of the accented note, louder than the rest of the music. Although this is mostly a quick change in dynamics, it usually affects the articulation of the note, too. The extra loudness of the note often requires a stronger, more definite attack at the beginning of the accented note, and it is emphasized by putting some space before and after the accented notes. The effect of a lot of accented notes in a row may sound marcato.

Figure 1.94. Accents

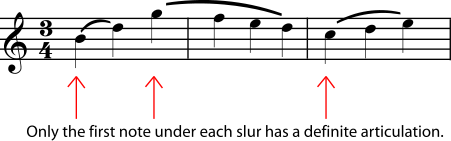

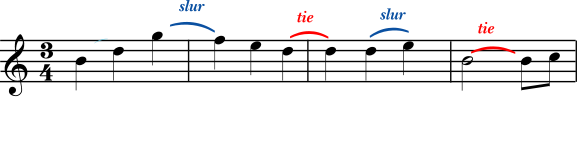

A slur is marked by a curved line joining any number of notes. When notes are slurred, only the first note under each slur marking has a definite articulation at the beginning. The rest of the notes are so seamlessly connected that there is no break between the notes. A good example of slurring occurs when a vocalist sings more than one note on the same syllable of text.

Figure 1.95. Slurs

A tie looks like a slur, but it is between two notes that are the same pitch. A tie is not really an articulation marking. It is included here because it looks like one, which can cause confusion for beginners. When notes are tied together, they are played as if they are one single note that is the length of all the notes that are tied together. (Please see Dots, Ties, and Borrowed Divisions.)

Figure 1.96. Slurs vs. Ties

A portamento is a smooth glide between the two notes, including all the pitches in between. For some instruments, like violin and trombone, this includes even the pitches in between the written notes. For other instruments, such as guitar, it means sliding through all of the possible notes between the two written pitches.

Figure 1.97. Portamento

Although unusual in traditional common notation, a type of portamento that includes only one written pitch can be found in some styles of music, notably jazz, blues, and rock. As the notation suggests, the proper performance of scoops and fall-offs requires that the portamento begins (in scoops) or ends (in fall-offs) with the slide itself, rather than with a specific note.

Figure 1.98. Scoops and Fall-offs

Some articulations may be some combination of staccato, legato, and accent. Marcato, for example means "marked" in the sense of "stressed" or "noticeable". Notes marked marcato have enough of an accent and/or enough space between them to make each note seem stressed or set apart. They are usually longer than staccato but shorter than legato. Other notes may be marked with a combination of articulation symbols, for example legato with accents. As always, the best way to perform such notes depends on the instrument and the style of the music.

Figure 1.99. Some Possible Combination Markings

Plenty of music has no articulation marks at all, or marks on only a few notes. Often, such music calls for notes that are a little more separate or defined than legato, but still nowhere as short as staccato. Mostly, though, it is up to the performer to know what is considered proper for a particular piece. For example, most ballads are sung legato, and most marches are played fairly staccato or marcato, whether they are marked that way or not. Furthermore, singing or playing a phrase with musicianship often requires knowing which notes of the phrase should be legato, which should be more separate, where to add a little portamento, and so on. This does not mean the best players consciously decide how to play each note. Good articulation comes naturally to the musician who has mastered the instrument and the style of the music.

1.2. Time

Duration: Note Lengths in Written Music*

The Shape of a Note

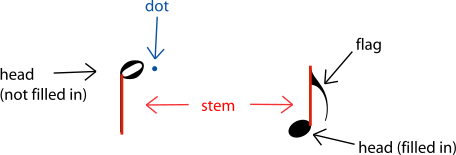

In standard notation, a single musical sound is written as a note. The two most important things a written piece of music needs to tell you about a note are its pitch - how high or low it is - and its duration - how long it lasts.

To find out the pitch of a written note, you look at the clef and the key signature, then see what line or space the note is on. The higher a note sits on the staff, the higher it sounds. To find out the duration of the written note, you look at the tempo and the time signature and then see what the note looks like.

Figure 1.43. The Parts of a Note

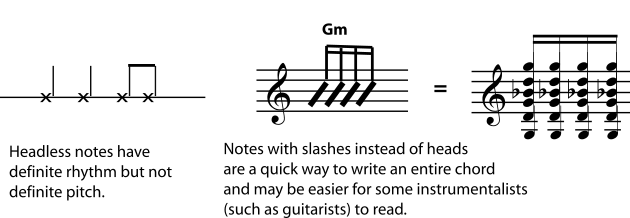

The pitch of the note depends only on what line or space the head of the note is on. (Please see pitch , clef and key signature for more information.) If the note does not have a head (see Figure 1.44), that means that it does not have one definite pitch.

Figure 1.44. Notes Without Heads

The head of the note may be filled in (black), or not. The note may also have (or not) a stem, one or more flags, beams connecting it to other notes, or one or more dots following the head of the note. All of these things affect how much time the note is given in the music.

A dot that is someplace other than next to the head of the note does not affect the rhythm. Other dots are articulation marks. They may affect the actual length of the note (the amount of time it sounds), but do not affect the amount of time it must be given. (The extra time when the note could be sounding, but isn't, becomes an unwritten rest.) If this is confusing, please see the explanation in articulation.

The Length of a Note

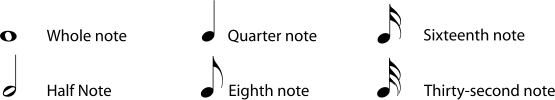

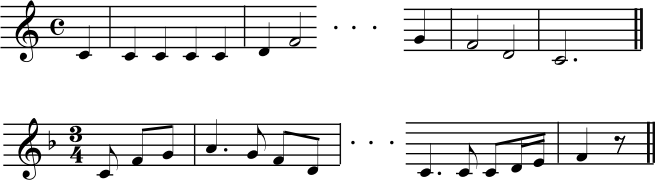

Figure 1.45. Most Common Note Lengths

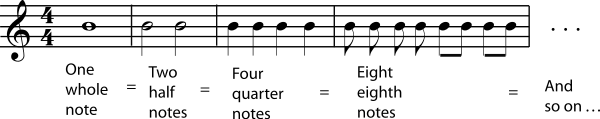

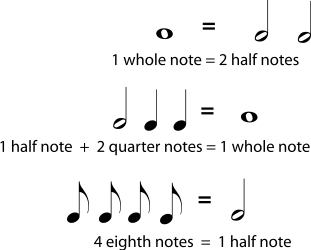

The simplest-looking note, with no stems or flags, is a whole note. All other note lengths are defined by how long they last compared to a whole note. A note that lasts half as long as a whole note is a half note. A note that lasts a quarter as long as a whole note is a quarter note. The pattern continues with eighth notes, sixteenth notes, thirty-second notes, sixty-fourth notes, and so on, each type of note being half the length of the previous type. (There are no such thing as third notes, sixth notes, tenth notes, etc.; see Dots, Ties, and Borrowed Divisions to find out how notes of unusual lengths are written.)

Figure 1.46.

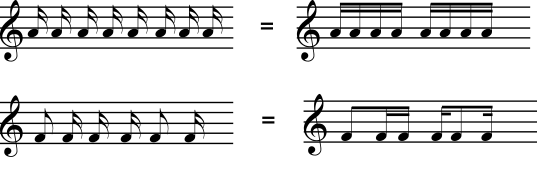

You may have noticed that some of the eighth notes in Figure 1.46 don't have flags; instead they have a beam connecting them to another eighth note. If flagged notes are next to each other, their flags can be replaced by beams that connect the notes into easy-to-read groups. The beams may connect notes that are all in the same beat, or, in some vocal music, they may connect notes that are sung on the same text syllable. Each note will have the same number of beams as it would have flags.

Figure 1.47. Notes with Beams

You may have also noticed that the note lengths sound like fractions in arithmetic. In fact they work very much like fractions: two half notes will be equal to (last as long as) one whole note; four eighth notes will be the same length as one half note; and so on. (For classroom activities relating music to fractions, see Fractions, Multiples, Beats, and Measures.)

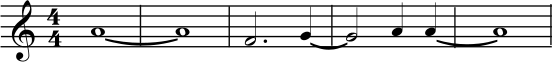

Example 1.2.

Figure 1.48.

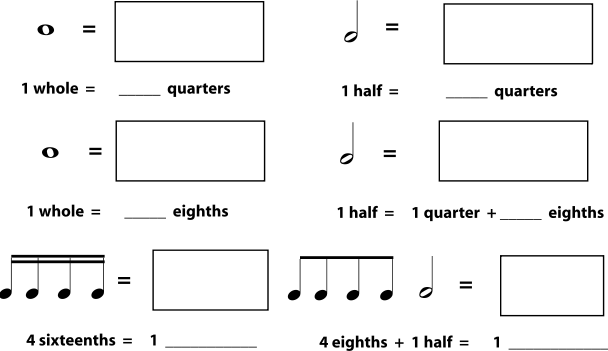

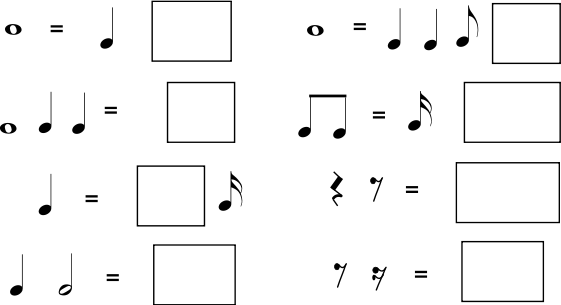

Exercise 1.6.1. (Go to Solution)

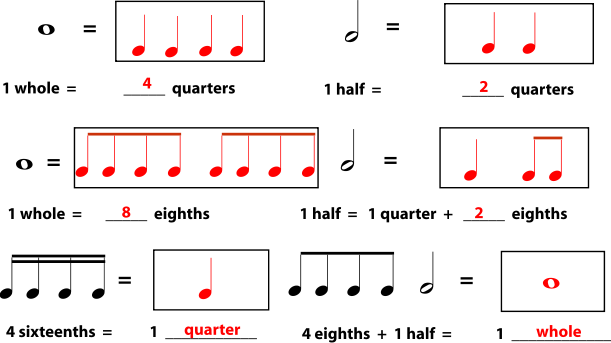

Draw the missing notes and fill in the blanks to make each side the same duration (length of time).

Figure 1.49.

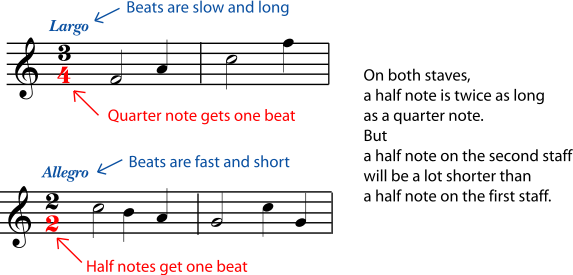

So how long does each of these notes actually last? That depends on a couple of things. A written note lasts for a certain amount of time measured in beats. To find out exactly how many beats it takes, you must know the time signature. And to find out how long a beat is, you need to know the tempo.

Example 1.3.

Figure 1.50.

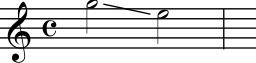

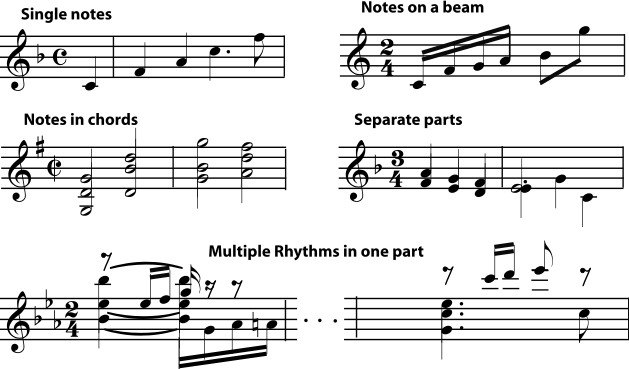

More about Stems

Whether a stem points up or down does not affect the note length at all. There are two basic ideas that lead to the rules for stem direction. One is that the music should be as easy as possible to read and understand. The other is that the notes should tend to be "in the staff" as much as reasonably possible.

Basic Stem Direction Rules

-

Single Notes - Notes below the middle line of the staff should be stem up. Notes on or above the middle line should be stem down.

-

Notes sharing a stem (block chords) - Generally, the stem direction will be the direction for the note that is furthest away from the middle line of the staff

-

Notes sharing a beam - Again, generally you will want to use the stem direction of the note farthest from the center of the staff, to keep the beam near the staff.

-

Different rhythms being played at the same time by the same player - Clarity requires that you write one rhythm with stems up and the other stems down.

-

Two parts for different performers written on the same staff - If the parts have the same rhythm, they may be written as block chords. If they do not, the stems for one part (the "high" part or "first" part) will point up and the stems for the other part will point down. This rule is especially important when the two parts cross; otherwise there is no way for the performers to know that the "low" part should be reading the high note at that spot.

Figure 1.51. Stem Direction

Solutions to Exercises

Duration: Rest Length*

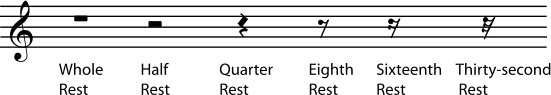

A rest stands for a silence in music. For each kind of note, there is a written rest of the same length.

Figure 1.53. The Most Common Rests

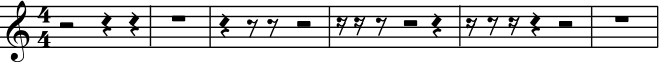

Exercise 1.7.1. (Go to Solution)

For each note on the first line, write a rest of the same length on the second line. The first measure is done for you.

Figure 1.54.

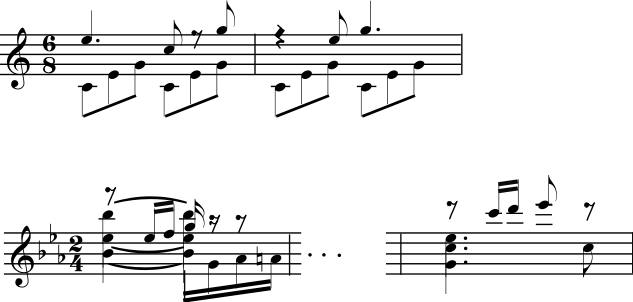

Rests don't necessarily mean that there is silence in the music at that point; only that that part is silent. Often, on a staff with multiple parts, a rest must be used as a placeholder for one of the parts, even if a single person is playing both parts. When the rhythms are complex, this is necessary to make the rhythm in each part clear.

Figure 1.55.

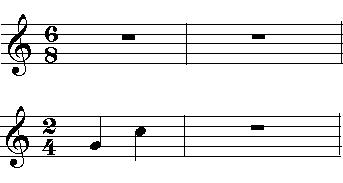

The normal rule in common notation is that, for any line of music, the notes and rests in each measure must "add up" to exactly the amount in the time signature, no more and no less. For example, in 3/4 time, a measure can have any combination of notes and rests that is the same length as three quarter notes. There is only one common exception to this rule. As a simplifying shorthand, a completely silent measure can simply have a whole rest. In this case, "whole rest" does not necessarily mean "rest for the same length of time as a whole note"; it means "rest for the entire measure".

Figure 1.56.

Solutions to Exercises

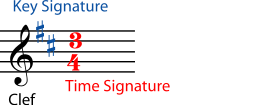

Time Signature*

The time signature appears at the beginning of a piece of music, right after the key signature. Unlike the key signature, which is on every staff, the time signature will not appear again in the music unless the meter changes. The meter of a piece of music is its basic rhythm; the time signature is the symbol that tells you the meter of the piece and how (with what type of note) it is written.

Figure 1.58.

Beats and Measures

Because music is heard over a period of time, one of the main ways music is organized is by dividing that time up into short periods called beats. In most music, things tend to happen right at the beginning of each beat. This makes the beat easy to hear and feel. When you clap your hands, tap your toes, or dance, you are "moving to the beat". Your claps are sounding at the beginning of the beat, too. This is also called being "on the downbeat", because it is the time when the conductor's baton hits the bottom of its path and starts moving up again.

Example 1.4.

Listen to excerpts A, B, C and D. Can you clap your hands, tap your feet, or otherwise move "to the beat"? Can you feel the 1-2-1-2 or 1-2-3-1-2-3 of the meter? Is there a piece in which it is easier or harder to feel the beat?

- Excerpt A:

- Excerpt B:

- Excerpt C:

- Excerpt D:

The downbeat is the strongest part of the beat, but some downbeats are stronger than others. Usually a pattern can be heard in the beats: strong-weak-weak-strong-weak-weak, or strong-weak-strong-weak. So beats are organized even further by grouping them into bars, or measures. (The two words mean the same thing.) For example, for music with a beat pattern of strong-weak-weak-strong-weak-weak, or 1-2-3-1-2-3, a measure would have three beats in it. The time signature tells you two things: how many beats there are in each measure, and what type of note gets a beat.

Figure 1.59. Reading the Time Signature

Exercise 1.8.1. (Go to Solution)

Listen again to the music in Example 1.4. Instead of clapping, count each beat. Decide whether the music has 2, 3, or 4 beats per measure. In other words, does it feel more natural to count 1-2-1-2, 1-2-3-1-2-3, or 1-2-3-4-1-2-3-4?

Meter: Reading Time Signatures

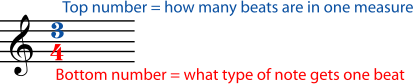

Most time signatures contain two numbers. The top number tells you how many beats there are in a measure. The bottom number tells you what kind of note gets a beat.

Figure 1.60.

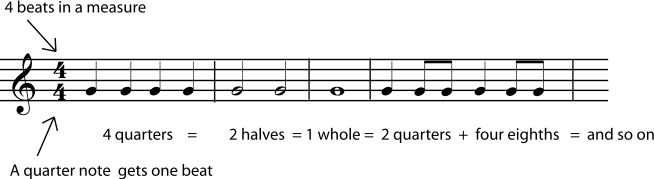

You may have noticed that the time signature looks a little like a fraction in arithmetic. Filling up measures feels a little like finding equivalent fractions, too. In "four four time", for example, there are four beats in a measure and a quarter note gets one beat. So four quarter notes would fill up one measure. But so would any other combination of notes that equals four quarters: one whole, two halves, one half plus two quarters, and so on.

Example 1.5.

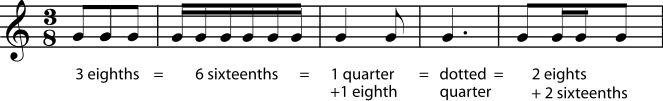

If the time signature is three eight, any combination of notes that adds up to three eighths will fill a measure. Remember that a dot is worth an extra half of the note it follows. Listen to the rhythms in Figure 1.61.

Figure 1.61.

Exercise 1.8.2. (Go to Solution)

Write each of the time signatures below (with a clef symbol) at the beginning of a staff. Write at least four measures of music in each time signature. Fill each measure with a different combination of note lengths. Use at least one dotted note on each staff.

-

Two four time

-

Three eight time

-

Six four time

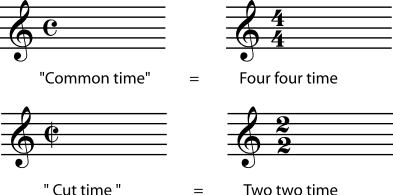

A few time signatures don't have to be written as numbers. Four four time is used so much that it is often called common time, written as a bold "C". When both fours are "cut" in half to twos, you have cut time, written as a "C" cut by a vertical slash.

Figure 1.62.

Counting and Conducting

You may have already noticed that a measure in four four time looks the same as a measure in two two. After all, in arithmetic, four quarters adds up to the same thing as two halves. For that matter, why not call the time signature "one one" or "eight eight"?

Figure 1.63.

Or why not write two two as two four, giving quarter notes the beat instead of half notes? The music would look very different, but it would sound the same, as long as you made the beats the same speed. The music in each of the staves in Figure 1.64 would sound like this.

Figure 1.64.

So why is one time signature chosen rather than another? The composer will normally choose a time signature that makes the music easy to read and also easy to count and conduct. Does the music feel like it has four beats in every measure, or does it go by so quickly that you only have time to tap your foot twice in a measure?

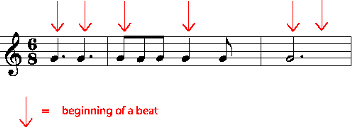

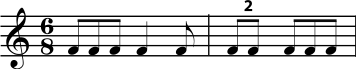

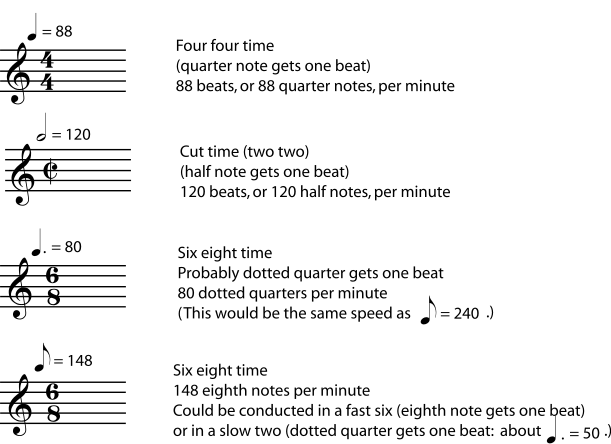

A common exception to this is six eight time, and the other time signatures (for example nine eight and twelve eight) commonly used to write compound meters. A piece in six eight might have six beats in every measure, with an eighth note getting a beat. But it is more likely that the conductor will give only two beats per measure, with a dotted quarter (or three eighth notes) getting one beat. Since beats normally get divided into halves and quarters, this is the easiest way for composers to write beats that are divided into thirds. In the same way, three eight may only have one beat per measure; nine eight, three beats per measure; and twelve eight, four beats per measure.

Figure 1.65.

Solutions to Exercises

Solution to Exercise 1.8.1. (Return to Exercise)

-

A has a very strong, quick 1-2-3 beat.

-

B is in a slow (easy) 2. You may feel it in a fast 4.

-

C is in a stately 4.

-

D is in 3, but the beat may be harder to feel than in A because the rhythms are more complex and the performer is taking some liberties with the tempo.

Solution to Exercise 1.8.2. (Return to Exercise)

There are an enormous number of possible note combinations for any time signature. That's one of the things that makes music interesting. Here are some possibilities. If you are not sure that yours are correct, check with your music instructor.

Figure 1.66.

Meter*

What is Meter?

The meter of a piece of music is the arrangment of its rhythms in a repetitive pattern of strong and weak beats. This does not necessarily mean that the rhythms themselves are repetitive, but they do strongly suggest a repeated pattern of pulses. It is on these pulses, the beat of the music, that you tap your foot, clap your hands, dance, etc.

Some music does not have a meter. Ancient music, such as Gregorian chants; new music, such as some experimental twentieth-century art music; and Non-Western music, such as some native American flute music, may not have a strong, repetitive pattern of beats. Other types of music, such as traditional Western African drumming, may have very complex meters that can be difficult for the beginner to identify.

But most Western music has simple, repetitive patterns of beats. This makes meter a very useful way to organize the music. Common notation, for example, divides the written music into small groups of beats called measures, or bars. The lines dividing each measure from the next help the musician reading the music to keep track of the rhythms. A piece (or section of the piece) is assigned a time signature that tells the performer how many beats to expect in each measure, and what type of note should get one beat. (For more on reading time signatures, please see Time Signature.)

Conducting also depends on the meter of the piece; conductors use different conducting patterns for the different meters. These patterns emphasize the differences between the stronger and weaker beats to help the performers keep track of where they are in the music.

But the conducting patterns depend only on the pattern of strong and weak beats. In other words, they only depend on "how many beats there are in a measure", not "what type of note gets a beat". So even though the time signature is often called the "meter" of a piece, one can talk about meter without worrying about the time signature or even being able to read music. (Teachers, note that this means that children can be introduced to the concept of meter long before they are reading music. See Meter Activities for some suggestions.)

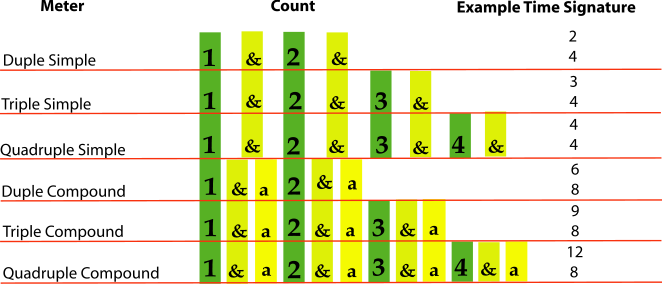

Classifying Meters

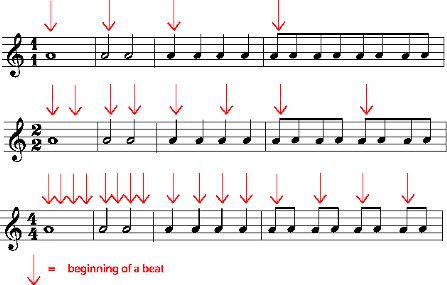

Meters can be classified by counting the number of beats from one strong beat to the next. For example, if the meter of the music feels like "strong-weak-strong-weak", it is in duple meter. "strong-weak-weak-strong-weak-weak" is triple meter, and "strong-weak-weak-weak" is quadruple. (Most people don't bother classifying the more unusual meters, such as those with five beats in a measure.)

Meters can also be classified as either simple or compound. In a simple meter, each beat is basically divided into halves. In compound meters, each beat is divided into thirds.

A borrowed division occurs whenever the basic meter of a piece is interrupted by some beats that sound like they are "borrowed" from a different meter. One of the most common examples of this is the use of triplets to add some compound meter to a piece that is mostly in a simple meter. (See Dots, Ties, and Borrowed Divisions to see what borrowed divisions look like in common notation.)

Recognizing Meters

To learn to recognize meter, remember that (in most Western music) the beats and the subdivisions of beats are all equal and even. So you are basically listening for a running, even pulse underlying the rhythms of the music. For example, if it makes sense to count along with the music "ONE-and-Two-and-ONE-and-Two-and" (with all the syllables very evenly spaced) then you probably have a simple duple meter. But if it's more comfortable to count "ONE-and-a-Two-and-a-ONE-and-a-Two-and-a", it's probably compound duple meter. (Make sure numbers always come on a pulse, and "one" always on the strongest pulse.)

This may take some practice if you're not used to it, but it can be useful practice for anyone who is learning about music. To help you get started, the figure below sums up the most-used meters. To help give you an idea of what each meter should feel like, here are some animations (with sound) of duple simple, duple compound, triple simple, triple compound, quadruple simple, and quadruple compound meters. You may also want to listen to some examples of music that is in simple duple, simple triple, simple quadruple, compound duple, and compound triple meters.

Figure 1.67. Meters

Pickup Notes and Measures*

Pickup Measures

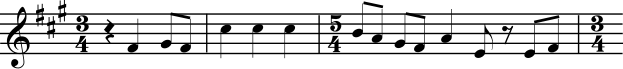

Normally, all the measures of a piece of music must have exactly the number of beats indicated in the time signature. The beats may be filled with any combination of notes or rests (with duration values also dictated by the time signature), but they must combine to make exactly the right number of beats. If a measure or group of measures has more or fewer beats, the time signature must change.

Figure 1.68.

There is one common exception to this rule. (There are also some less common exceptions not discussed here.) Often, a piece of music does not begin on the strongest downbeat. Instead, the strong beat that people like to count as "one" (the beginning of a measure), happens on the second or third note, or even later. In this case, the first measure may be a full measure that begins with some rests. But often the first measure is simply not a full measure. This shortened first measure is called a pickup measure.

If there is a pickup measure, the final measure of the piece should be shortened by the length of the pickup measure (although this rule is sometimes ignored in less formal written music). For example, if the meter of the piece has four beats, and the pickup measure has one beat, then the final measure should have only three beats. (Of course, any combination of notes and rests can be used, as long as the total in the first and final measures equals one full measure.

Figure 1.69.

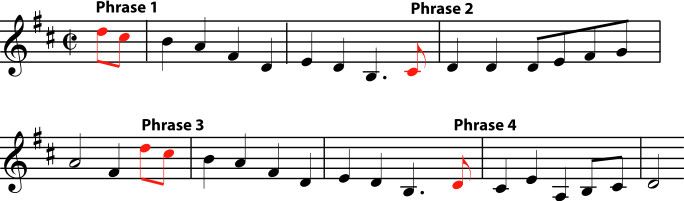

Pickup Notes

Any phrase of music (not just the first one) may begin someplace other than on a strong downbeat. All the notes before the first strong downbeat of any phrase are the pickup notes to that phrase.

Figure 1.70.

A piece that is using pickup measures or pickup notes may also sometimes place a double bar (with or without repeat signs) inside a measure, in order to make it clear which phrase and which section of the music the pickup notes belong to. If this happens (which is a bit rare, because it can be confusing to read), there is still a single bar line where it should be, at the end of the measure.

Figure 1.71.

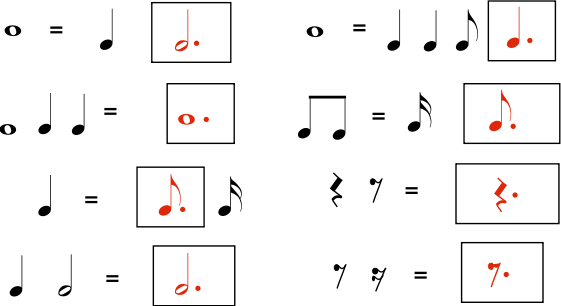

Dots, Ties, and Borrowed Divisions*

A half note is half the length of a whole note; a quarter note is half the length of a half note; an eighth note is half the length of a quarter note, and so on. (See Duration:Note Length.) The same goes for rests. (See Duration: Rest Length.) But what if you want a note (or rest) length that isn't half of another note (or rest) length?

Dotted Notes

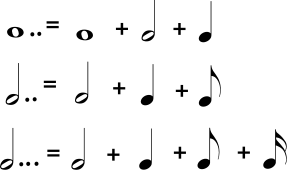

One way to get a different length is by dotting the note or rest. A dotted note is one-and-a-half times the length of the same note without the dot. In other words, the note keeps its original length and adds another half of that original length because of the dot. So a dotted half note, for example, would last as long as a half note plus a quarter note, or three quarters of a whole note.

Figure 1.72.

Exercise 1.11.1. (Go to Solution)

Make groups of equal length on each side, by putting a dotted note or rest in the box.

Figure 1.73.

A note may have more than one dot. Each dot adds half the length that the dot before it added. For example, the first dot after a half note adds a quarter note length; the second dot would add an eighth note length.

Figure 1.74.

Tied Notes

A dotted half lasts as long as a half note plus a quarter note. The same length may be written as a half note and a quarter note tied together. Tied notes are written with a curved line connecting two notes that are on the same line or the same space in the staff. Notes of any length may be tied together, and more than two notes may be tied together. The sound they stand for will be a single note that is the length of all the tied notes added together. This is another way to make a great variety of note lengths. Tied notes are also the only way to write a sound that starts in one measure and ends in a different measure.

Ties may look like slurs, but they are not the same; a slur connects to notes with different pitches and is a type of articulation.

Figure 1.75.

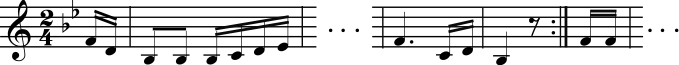

Borrowed Divisions

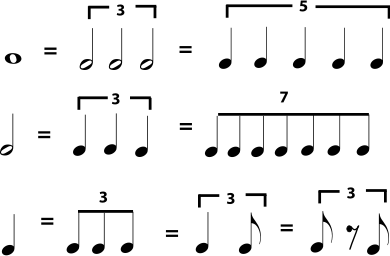

Dots and ties give you much freedom to write notes of varying lengths, but so far you must build your notes from halves of other notes. If you want to divide a note length into anything other than halves or halves of halves - if you want to divide a beat into thirds or fifths, for example - you must write the number of the division over the notes. These unusual subdivisions are called borrowed divisions because they sound as if they have been borrowed from a completely different meter. They can be difficult to perform correctly and are avoided in music for beginners. The only one that is commonly used is triplets, which divide a note length into equal thirds.

Figure 1.76. Some Borrowed Divisions

Figure 1.77. Borrowed Duplets

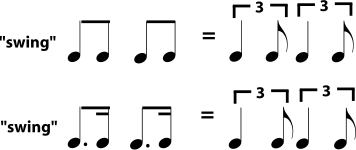

Notes in jazzy-sounding music that has a "swing" beat are often assumed to be triplet rhythms, even when they look like regular divisions; for example, two written eighth notes (or a dotted quarter-sixteenth) might sound like a triplet quarter-eighth rhythm. In jazz and other popular music styles, a tempo notation that says swing usually means that all rhythms should be played as triplets. Straight means to play the rhythms as written.

Some jazz musicians prefer to think of a swing rhythm as more of a heavy accent on the second eighth, rather than as a triplet rhythm, particularly when the tempo is fast. This distinction is not important for students of music theory, but jazz students will want to work hard on using both rhythm and articulation to produce a convincing "swing".

Figure 1.78. Swing Rhythms

Solutions to Exercises

Syncopation*

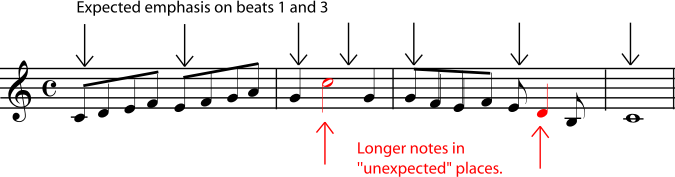

A syncopation or syncopated rhythm is any rhythm that puts an emphasis on a beat, or a subdivision of a beat, that is not usually emphasized. One of the most obvious features of Western music, to be heard in most everything from Bach to blues, is a strong, steady beat that can easily be grouped evenly into measures. (In other words, each measure has the same number of beats, and you can hear the measures in the music because the first beat of the measure is the strongest. See Time Signature and Meter for more on this.) This makes it easy for you to dance or clap your hands to the music. But music that follows the same rhythmic pattern all the time can get pretty boring. Syncopation is one way to liven things up. The music can suddenly emphasize the weaker beats of the measure, or it can even emphasize notes that are not on the beat at all. For example, listen to the melody in Figure 1.80.

Figure 1.80.

The first measure clearly establishes a simple quadruple meter ("ONE and two and THREE and four and"), in which important things, like changes in the melody, happen on beat one or three. But then, in the second measure, a syncopation happens; the longest and highest note is on beat two, normally a weak beat. In the syncopation in the third measure, the longest note doesn't even begin on a beat; it begins half-way through the third beat. (Some musicians would say "on the up-beat" or "on the 'and' of three".) Now listen to another example from a Boccherini minuet. Again, some of the long notes begin half-way between the beats, or "on the up-beat". Notice, however, that in other places in the music, the melody establishes the meter very strongly, so that the syncopations are easily heard to be syncopations.

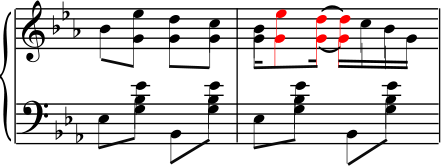

Figure 1.81.

Another way to strongly establish the meter is to have the syncopated rhythm playing in one part of the music while another part plays a more regular rhythm, as in this passage from Scott Joplin (see Figure 1.81). Syncopations can happen anywhere: in the melody, the bass line, the rhythm section, the chordal accompaniment. Any spot in the rhythm that is normally weak (a weak beat, an upbeat, a sixteenth of a beat, a part of a triplet) can be given emphasis by a syncopation. It can suddenly be made important by a long or high note in the melody, a change in direction of the melody, a chord change, or a written accent. Depending on the tempo of the music and the type of syncopation, a syncopated rhythm can make the music sound jaunty, jazzy, unsteady, surprising, uncertain, exciting, or just more interesting.

Other musical traditions tend to be more rhythmically complex than Western music, and much of the syncopation in modern American music is due to the influence of Non-Western traditions, particularly the African roots of the African-American tradition. Syncopation is such an important aspect of much American music, in fact, that the type of syncopation used in a piece is one of the most important clues to the style and genre of the music. Ragtime, for example, would hardly be ragtime without the jaunty syncopations in the melody set against the steady unsyncopated bass. The "swing" rhythm in big-band jazz and the "back-beat" of many types of rock are also specific types of syncopation. If you want practice hearing syncopations, listen to some ragtime or jazz. Tap your foot to find the beat, and then notice how often important musical "events" are happening "in between" your foot-taps.

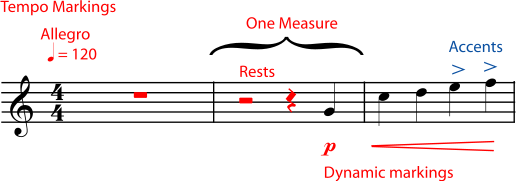

Tempo*

The tempo of a piece of music is its speed. There are two ways to specify a tempo. Metronome markings are absolute and specific. Other tempo markings are verbal descriptions which are more relative and subjective. Both types of markings usually appear above the staff, at the beginning of the piece, and then at any spot where the tempo changes. Markings that ask the player to deviate slightly from the main tempo, such as ritardando may appear either above or below the staff.

Metronome Markings

Metronome markings are given in beats per minute. They can be estimated using a clock with a second hand, but the easiest way to find them is with a metronome, which is a tool that can give a beat-per-minute tempo as a clicking sound or a pulse of light. Figure 1.83 shows some examples of metronome markings.

Figure 1.83.

Metronomes often come with other tempo indications written on them, but this is misleading. For example, a metronome may have allegro marked at 120 beats per minute and andante marked at 80 beats per minute. Allegro should certainly be quite a bit faster than andante, but it may not be exactly 120 beats per minute.

Tempo Terms

A tempo marking that is a word or phrase gives you the composer's idea of how fast the music should feel. How fast a piece of music feels depends on several different things, including the texture and complexity of the music, how often the beat gets divided into faster notes, and how fast the beats themselves are (the metronome marking). Also, the same tempo marking can mean quite different things to different composers; if a metronome marking is not available, the performer should use a knowledge of the music's style and genre, and musical common sense, to decide on the proper tempo. When possible, listening to a professional play the piece can help with tempo decisions, but it is also reasonable for different performers to prefer slightly different tempos for the same piece.

Traditionally, tempo instructions are given in Italian.

Some Common Tempo Markings

-

Grave - very slow and solemn (pronounced "GRAH-vay")

-

Largo - slow and broad ("LAR-go")

-

Larghetto - not quite as slow as largo ("lar-GET-oh")

-

Adagio - slow ("uh-DAH-jee-oh")

-

Lento - slow ("LEN-toe")

-

Andante - literally "walking", a medium slow tempo ("on-DON-tay")

-

Moderato - moderate, or medium ("MOD-er-AH-toe")

-

Allegretto - Not as fast as allegro ("AL-luh-GRET-oh")

-

Allegro - fast ("uh-LAY-grow")

-

Vivo, or Vivace - lively and brisk ("VEE-voh")

-

Presto - very fast ("PRESS-toe")

-

Prestissimo - very, very fast ("press-TEE-see-moe")

These terms, along with a little more Italian, will help you decipher most tempo instructions.

More useful Italian

-

(un) poco - a little ("oon POH-koe")

-

molto - a lot ("MOLE-toe")

-

piu - more ("pew")

-

meno - less ("MAY-no")

-

mosso - literally "moved"; motion or movement ("MOE-so")

Exercise 1.13.1. (Go to Solution)

Check to see how comfortable you are with Italian tempo markings by translating the following.

-

un poco allegro

-

molto meno mosso

-

piu vivo

-

molto adagio

-

poco piu mosso

Of course, tempo instructions don't have to be given in Italian. Much folk, popular, and modern music, gives instructions in English or in the composer's language. Tempo indications such as "Not too fast", "With energy", "Calmly", or "March tempo" give a good idea of how fast the music should feel.

Gradual Tempo Changes

If the tempo of a piece of music suddenly changes into a completely different tempo, there will be a new tempo given, usually marked in the same way (metronome tempo, Italian term, etc.) as the original tempo. Gradual changes in the basic tempo are also common in music, though, and these have their own set of terms. These terms often appear below the staff, although writing them above the staff is also allowed. These terms can also appear with modifiers like molto or un poco. You may notice that there are quite a few terms for slowing down. Again, the use of these terms will vary from one composer to the next; unless beginning and ending tempo markings are included, the performer must simply use good musical judgement to decide how much to slow down in a particular ritardando or rallentando.

Gradual Tempo Changes

-

accelerando - (abbreviated accel.) accelerating; getting faster

-

ritardando - (abbrev. rit.) slowing down

-

ritenuto - (abbrev. riten.) slower

-

rallentando - (abbrev. rall.) gradually slower

-

rubato - don't be too strict with the rhythm; while keeping the basic tempo, allow the music to gently speed up and relax in ways that emphasize the phrasing

-

poco a poco - little by little; gradually

-

Tempo I - ("tempo one" or "tempo primo") back to the original tempo (this instruction usually appears above the staff)

Solutions to Exercises

Solution to Exercise 1.13.1. (Return to Exercise)

-

a little fast

-

much less motion = much slower

-

more lively = faster

-

very slow

-

a little more motion = a little faster

Repeats and Other Musical Road Map Signs*

Repetition, either exact or with small or large variations, is one of the basic organizing principles of music. Repeated notes, motifs, phrases, melodies, rhythms, chord progressions, and even entire repeated sections in the overall form, are all very crucial in helping the listener make sense of the music. So good music is surprisingly repetitive!

So, in order to save time, ink, and page turns, common notation has many ways to show that a part of the music should be repeated exactly.

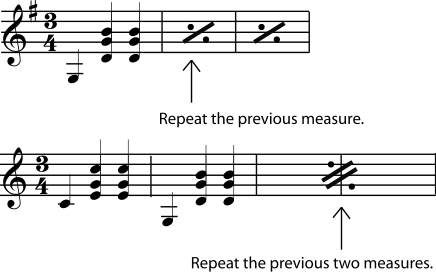

If the repeated part is very small - only one or two measures, for example - the repeat sign will probably look something like those in Figure 1.84. If you have very many such repeated measures in a row, you may want to number them (in pencil) to help you keep track of where you are in the music.

Figure 1.84. Repeated Measures

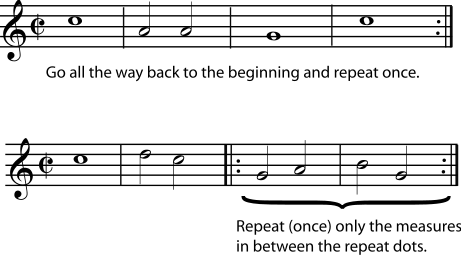

For repeated sections of medium length - usually four to thirty-two measures - repeat dots with or without endings are the most common markings. Dots to the right of a double bar line begin the repeated section; dots to the left of a double bar line end it. If there are no beginning repeat dots, you should go all the way back to the beginning of the music and repeat from there.

Figure 1.85. Repeat Dots

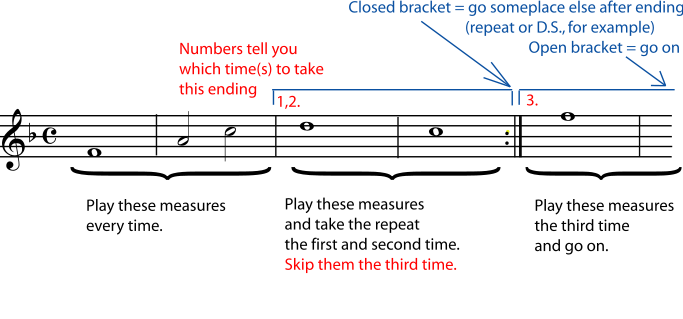

It is very common for longer repeated sections of music to be repeated exactly until the last few measures. When this happens, the repeat dots will be put in an ending. The bracket over the music shows you which measures to play each time you arrive at that point in the music. For example, the second time you reach a set of endings, you will skip the music in all the other endings; play only the measures in the second ending, and then do whatever the second ending directs you to do (repeat, go on, skip to somewhere else, etc.).

Figure 1.86. Repeat Endings

When you are repeating large sections in more informally written music, you may simply find instructions in the music such as "to refrain", "to bridge", "to verses", etc. Or you may find extra instructions to play certain parts "only on the repeat". Usually these instructions are reasonably clear, although you may need to study the music for a minute to get the "road map" clear in your mind. Pencilled-in markings can be a big help if it's difficult to spot the place you need to skip to. In order to help clarify things, repeat dots and other repeat instructions are almost always marked by a double bar line.

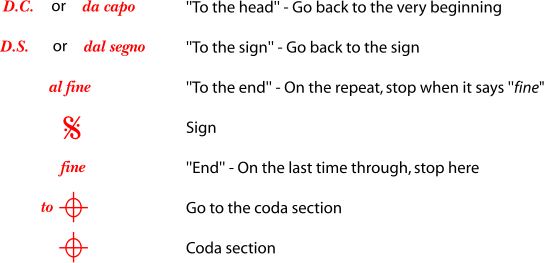

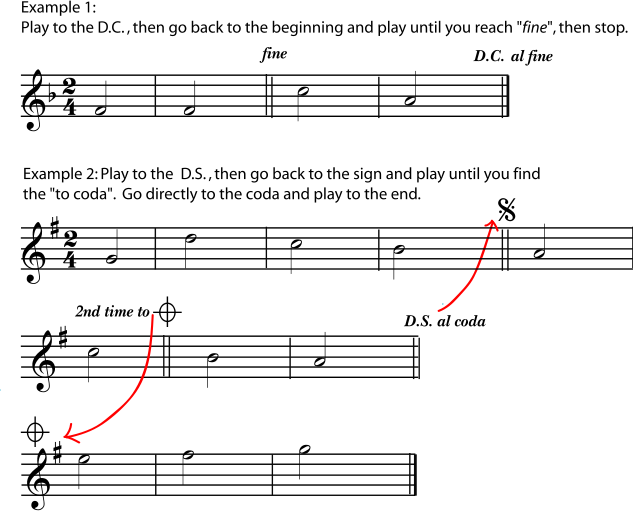

In Western classical music, the most common instructions for repeating large sections are traditionally written (or abbreviated) in Italian. The most common instructions from that tradition are in Figure 1.87.

Figure 1.87. Other Common "Road Map" Signs

Again, instructions can easily get quite complicated, and these large-section markings may require you to study your part for a minute to see how it is laid out, and even to mark (in pencil) circles and arrows that help you find the way quickly while you are playing. Figure 1.88 contains a few very simplistic examples of how these "road map signs" will work.

Figure 1.88.

1.1. Pitch

The Staff*

People were talking long before they invented writing. People were also making music long before anyone wrote any music down. Some musicians still play "by ear" (without written music), and some music traditions rely more on improvisation and/or "by ear" learning. But written music is very useful, for many of the same reasons that written words are useful. Music is easier to study and share if it is written down. Western music specializes in long, complex pieces for large groups of musicians singing or playing parts exactly as a composer intended. Without written music, this would be too difficult. Many different types of music notation have been invented, and some, such as tablature, are still in use. By far the most widespread way to write music, however, is on a staff. In fact, this type of written music is so ubiquitous that it is called common notation.

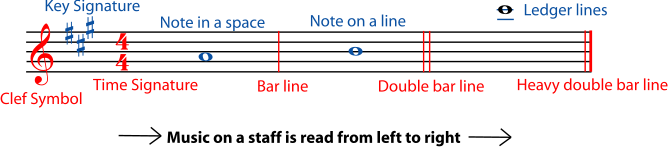

The Staff

The staff (plural staves) is written as five horizontal parallel lines. Most of the notes of the music are placed on one of these lines or in a space in between lines. Extra ledger lines may be added to show a note that is too high or too low to be on the staff. Vertical bar lines divide the staff into short sections called measures or bars. A double bar line, either heavy or light, is used to mark the ends of larger sections of music, including the very end of a piece, which is marked by a heavy double bar.

Figure 1.1. The Staff

Many different kinds of symbols can appear on, above, and below the staff. The notes and rests are the actual written music. A note stands for a sound; a rest stands for a silence. Other symbols on the staff, like the clef symbol, the key signature, and the time signature, tell you important information about the notes and measures. Symbols that appear above and below the music may tell you how fast it goes (tempo markings), how loud it should be (dynamic markings), where to go next (repeats, for example) and even give directions for how to perform particular notes (accents, for example).

Figure 1.2. Other Symbols on the Staff

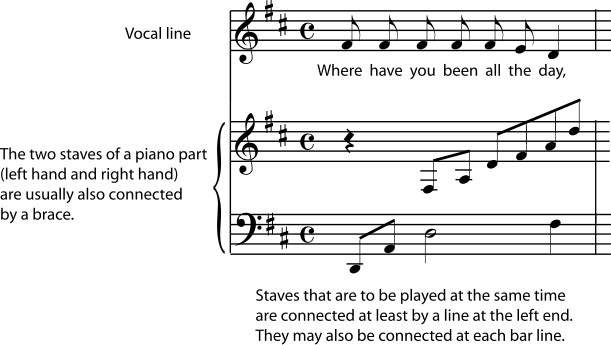

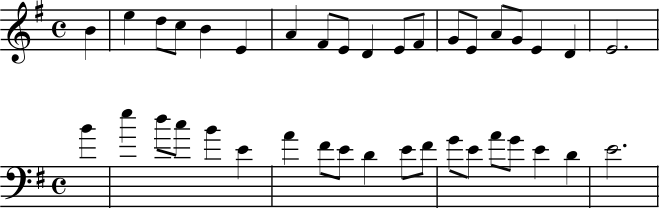

Groups of staves

Staves are read from left to right. Beginning at the top of the page, they are read one staff at a time unless they are connected. If staves should be played at the same time (by the same person or by different people), they will be connected at least by a long vertical line at the left hand side. They may also be connected by their bar lines. Staves played by similar instruments or voices, or staves that should be played by the same person (for example, the right hand and left hand of a piano part) may be grouped together by braces or brackets at the beginning of each line.

Figure 1.3. Groups of Staves

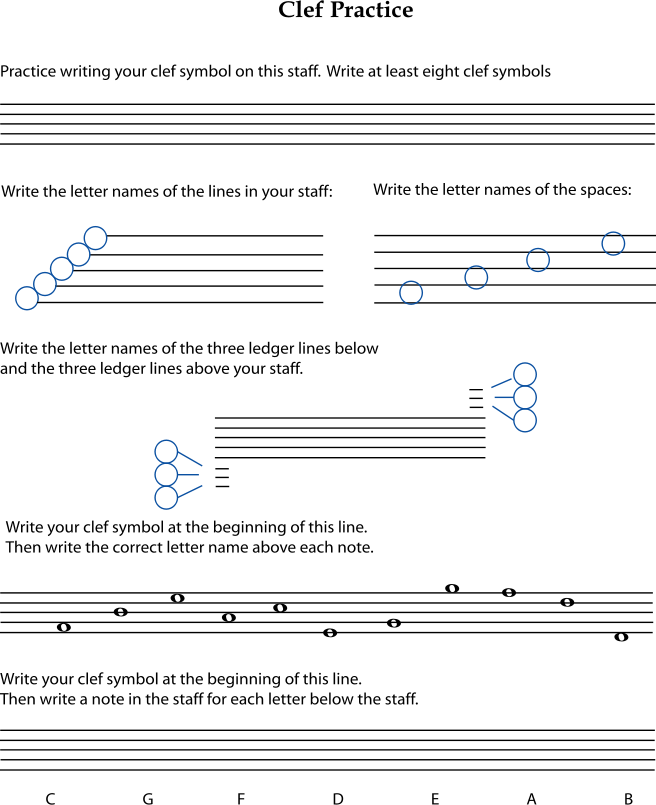

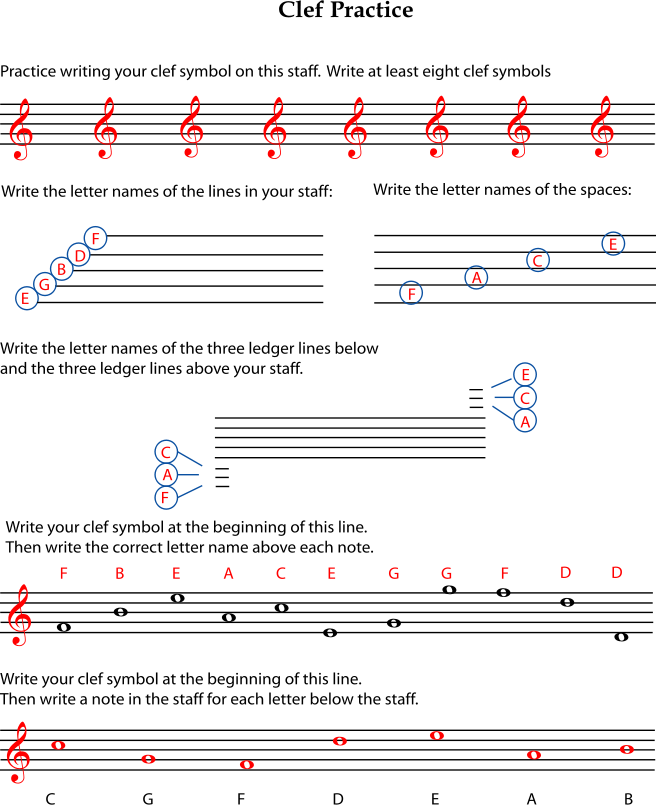

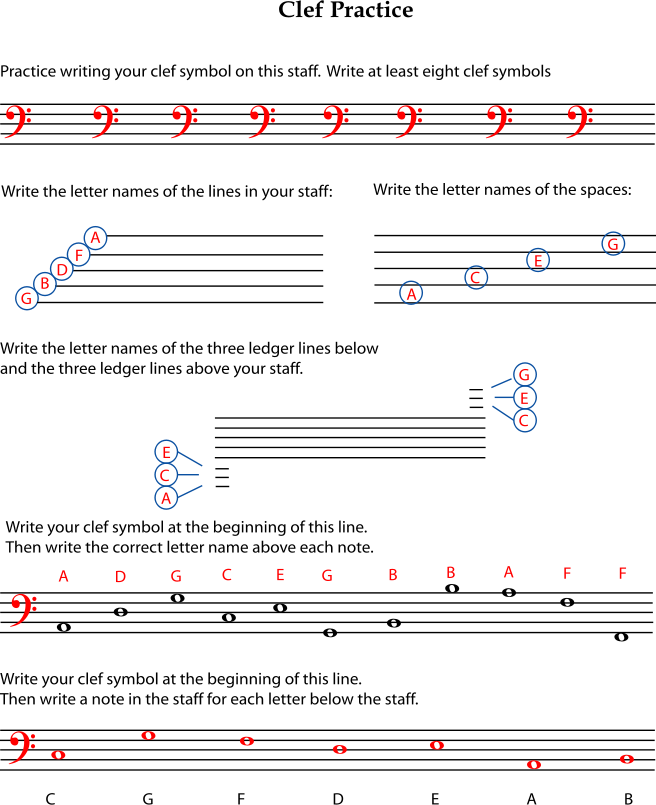

Clef*

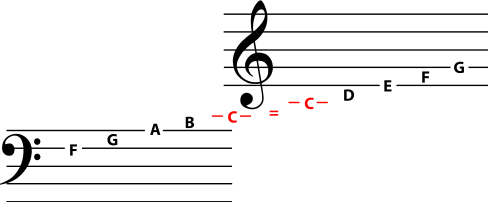

Treble Clef and Bass Clef

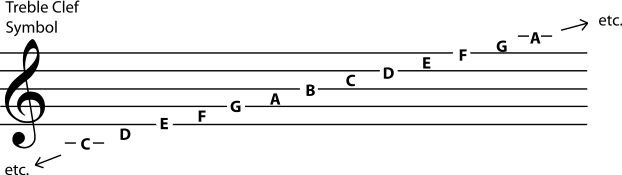

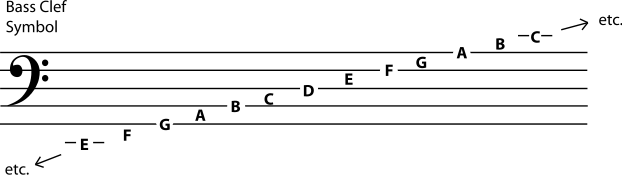

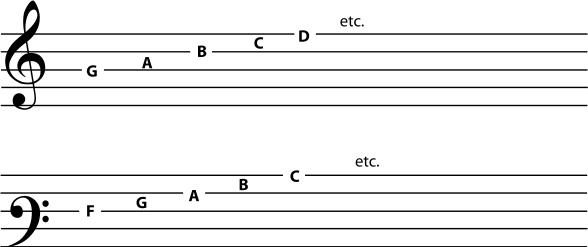

The first symbol that appears at the beginning of every music staff is a clef symbol. It is very important because it tells you which note (A, B, C, D, E, F, or G) is found on each line or space. For example, a treble clef symbol tells you that the second line from the bottom (the line that the symbol curls around) is "G". On any staff, the notes are always arranged so that the next letter is always on the next higher line or space. The last note letter, G, is always followed by another A.

Figure 1.4. Treble Clef

A bass clef symbol tells you that the second line from the top (the one bracketed by the symbol's dots) is F. The notes are still arranged in ascending order, but they are all in different places than they were in treble clef.

Figure 1.5. Bass Clef

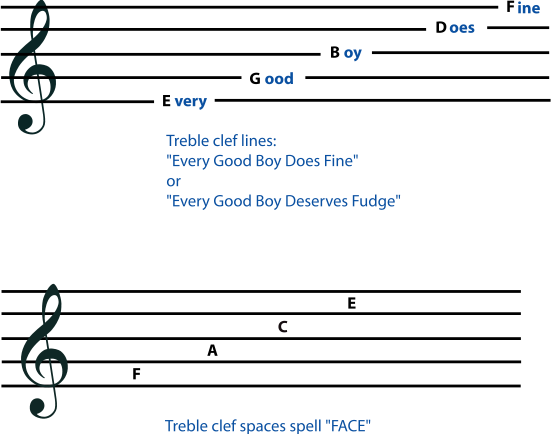

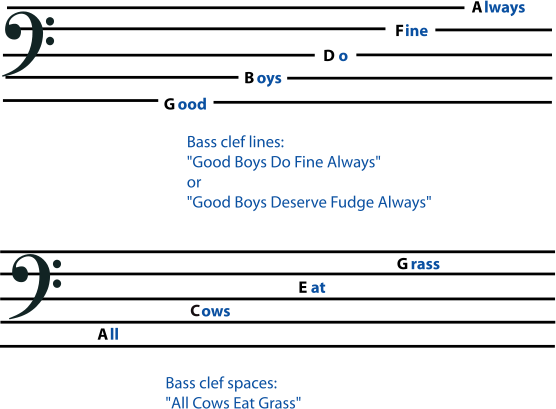

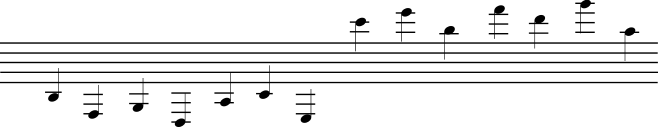

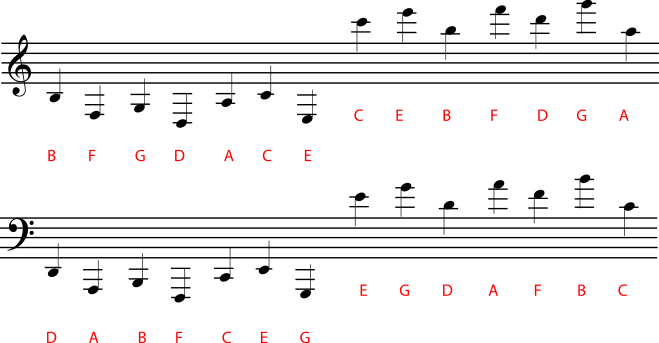

Memorizing the Notes in Bass and Treble Clef

One of the first steps in learning to read music in a particular clef is memorizing where the notes are. Many students prefer to memorize the notes and spaces separately. Here are some of the most popular mnemonics used.

Figure 1.6.

Moveable Clefs

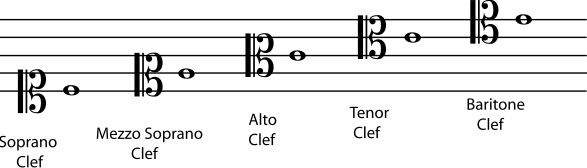

Most music these days is written in either bass clef or treble clef, but some music is written in a C clef. The C clef is moveable: whatever line it centers on is a middle C.

Figure 1.7. C Clefs

The bass and treble clefs were also once moveable, but it is now very rare to see them anywhere but in their standard positions. If you do see a treble or bass clef symbol in an unusual place, remember: treble clef is a G clef; its spiral curls around a G. Bass clef is an F clef; its two dots center around an F.

Figure 1.8. Moveable G and F Clefs

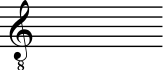

Much more common is the use of a treble clef that is meant to be read one octave below the written pitch. Since many people are uncomfortable reading bass clef, someone writing music that is meant to sound in the region of the bass clef may decide to write it in the treble clef so that it is easy to read. A very small "8" at the bottom of the treble clef symbol means that the notes should sound one octave lower than they are written.

Figure 1.9.

Why use different clefs?

Music is easier to read and write if most of the notes fall on the staff and few ledger lines have to be used.

Figure 1.10.

The G indicated by the treble clef is the G above middle C, while the F indicated by the bass clef is the F below middle C. (C clef indicates middle C.) So treble clef and bass clef together cover many of the notes that are in the range of human voices and of most instruments. Voices and instruments with higher ranges usually learn to read treble clef, while voices and instruments with lower ranges usually learn to read bass clef. Instruments with ranges that do not fall comfortably into either bass or treble clef may use a C clef or may be transposing instruments.

Figure 1.11.

Exercise 1.2.2. (Go to Solution)

Choose a clef in which you need to practice recognizing notes above and below the staff in Figure 1.13. Write the clef sign at the beginning of the staff, and then write the correct note names below each note.

Figure 1.13.

Solutions to Exercises

Solution to Exercise 1.2.2. (Return to Exercise)

Figure 1.16 shows the answers for treble and bass clef. If you have done another clef, have your teacher check your answers.

Figure 1.16.

Solution to Exercise 1.2.3. (Return to Exercise)

Figure 1.17 shows the answers for treble clef, and Figure 1.18 the answers for bass clef. If you are working in a more unusual clef, have your teacher check your answers.

Figure 1.17.

Figure 1.18.

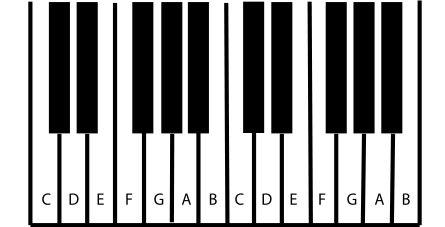

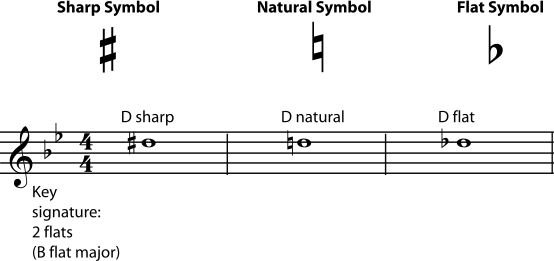

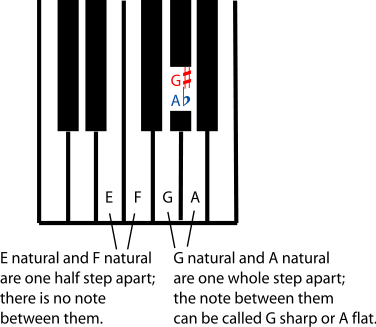

Pitch: Sharp, Flat, and Natural Notes*

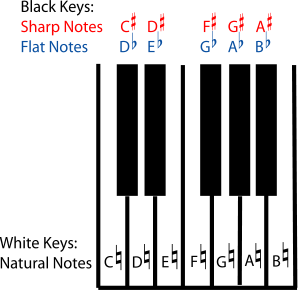

The pitch of a note is how high or low it sounds. Pitch depends on the frequency of the fundamental sound wave of the note. The higher the frequency of a sound wave, and the shorter its wavelength, the higher its pitch sounds. But musicians usually don't want to talk about wavelengths and frequencies. Instead, they just give the different pitches different letter names: A, B, C, D, E, F, and G. These seven letters name all the natural notes (on a keyboard, that's all the white keys) within one octave. (When you get to the eighth natural note, you start the next octave on another A.)

Figure 1.19.

But in Western music there are twelve notes in each octave that are in common use. How do you name the other five notes (on a keyboard, the black keys)?

Figure 1.20.

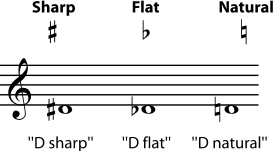

A sharp sign means "the note that is one half step higher than the natural note". A flat sign means "the note that is one half step lower than the natural note". Some of the natural notes are only one half step apart, but most of them are a whole step apart. When they are a whole step apart, the note in between them can only be named using a flat or a sharp.

Figure 1.21.

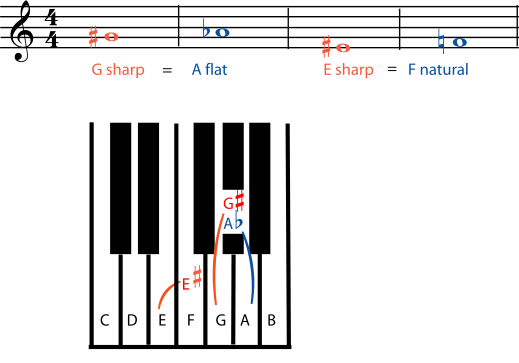

Notice that, using flats and sharps, any pitch can be given more than one note name. For example, the G sharp and the A flat are played on the same key on the keyboard; they sound the same. You can also name and write the F natural as "E sharp"; F natural is the note that is a half step higher than E natural, which is the definition of E sharp. Notes that have different names but sound the same are called enharmonic notes.

Figure 1.22.

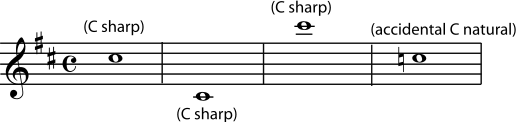

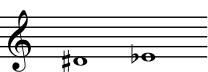

Sharp and flat signs can be used in two ways: they can be part of a key signature, or they can mark accidentals. For example, if most of the C's in a piece of music are going to be sharp, then a sharp sign is put in the "C" space at the beginning of the staff, in the key signature. If only a few of the C's are going to be sharp, then those C's are marked individually with a sharp sign right in front of them. Pitches that are not in the key signature are called accidentals.

Figure 1.23.

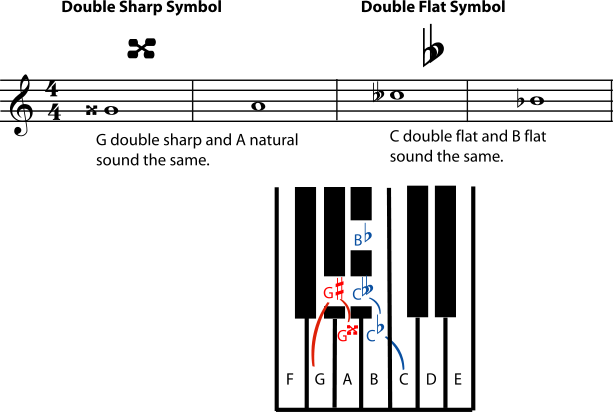

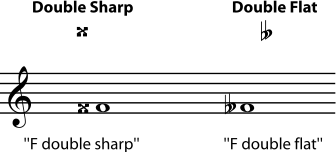

A note can also be double sharp or double flat. A double sharp is two half steps (one whole step) higher than the natural note; a double flat is two half steps (a whole step) lower. Triple, quadruple, etc. sharps and flats are rare, but follow the same pattern: every sharp or flat raises or lowers the pitch one more half step.

Using double or triple sharps or flats may seem to be making things more difficult than they need to be. Why not call the note "A natural" instead of "G double sharp"? The answer is that, although A natural and G double sharp are the same pitch, they don't have the same function within a particular chord or a particular key. For musicians who understand some music theory (and that includes most performers, not just composers and music teachers), calling a note "G double sharp" gives important and useful information about how that note functions in the chord and in the progression of the harmony.

Figure 1.24.

Key Signature*

Do key signatures make music more complicated than it needs to be? Is there an easier way? Join the discussion at Opening Measures.

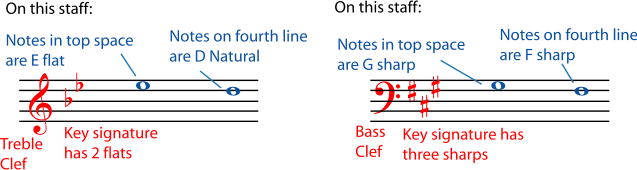

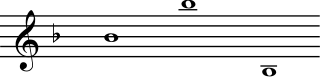

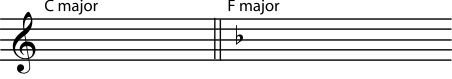

The key signature comes right after the clef symbol on the staff. It may have either some sharp symbols on particular lines or spaces, or some flat symbols, again on particular lines or spaces. If there are no flats or sharps listed after the clef symbol, then the key signature is "all notes are natural".

In common notation, clef and key signature are the only symbols that normally appear on every staff. They appear so often because they are such important symbols; they tell you what note is on each line and space of the staff. The clef tells you the letter name of the note (A, B, C, etc.), and the key tells you whether the note is sharp, flat or natural.

Figure 1.25.

The key signature is a list of all the sharps and flats in the key that the music is in. When a sharp (or flat) appears on a line or space in the key signature, all the notes on that line or space are sharp (or flat), and all other notes with the same letter names in other octaves are also sharp (or flat).

Figure 1.26.

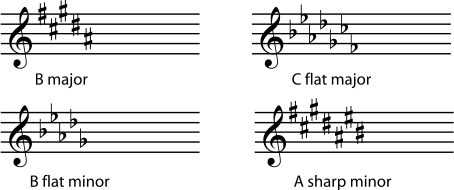

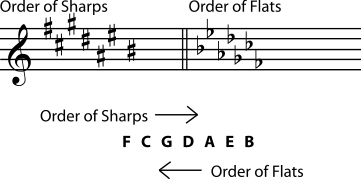

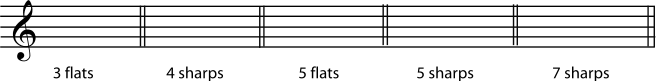

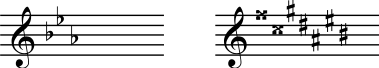

The sharps or flats always appear in the same order in all key signatures. This is the same order in which they are added as keys get sharper or flatter. For example, if a key (G major or E minor) has only one sharp, it will be F sharp, so F sharp is always the first sharp listed in a sharp key signature. The keys that have two sharps (D major and B minor) have F sharp and C sharp, so C sharp is always the second sharp in a key signature, and so on. The order of sharps is: F sharp, C sharp, G sharp, D sharp, A sharp, E sharp, B sharp. The order of flats is the reverse of the order of sharps: B flat, E flat, A flat, D flat, G flat, C flat, F flat. So the keys with only one flat (F major and D minor) have a B flat; the keys with two flats (B flat major and G minor) have B flat and E flat; and so on. The order of flats and sharps, like the order of the keys themselves, follows a circle of fifths.

Figure 1.27.

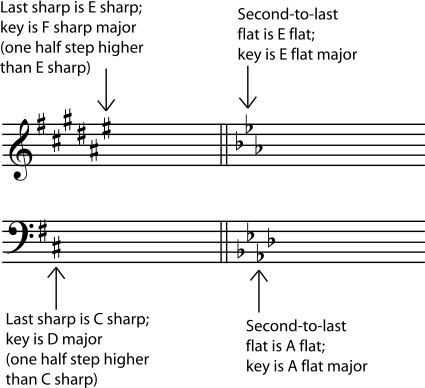

If you do not know the name of the key of a piece of music, the key signature can help you find out. Assume for a moment that you are in a major key. If the key contains sharps, the name of the key is one half step higher than the last sharp in the key signature. If the key contains flats, the name of the key signature is the name of the second-to-last flat in the key signature.

Example 1.1.

Figure 1.28 demonstrates quick ways to name the (major) key simply by looking at the key signature. In flat keys, the second-to-last flat names the key. In sharp keys, the note that names the key is one half step above the final sharp.

Figure 1.28.

The only major keys that these rules do not work for are C major (no flats or sharps) and F major (one flat). It is easiest just to memorize the key signatures for these two very common keys. If you want a rule that also works for the key of F major, remember that the second-to-last flat is always a perfect fourth higher than (or a perfect fifth lower than) the final flat. So you can also say that the name of the key signature is a perfect fourth lower than the name of the final flat.

Figure 1.29.

If the music is in a minor key, it will be in the relative minor of the major key for that key signature. You may be able to tell just from listening (see Major Keys and Scales) whether the music is in a major or minor key. If not, the best clue is to look at the final chord. That chord (and often the final note of the melody, also) will usually name the key.

Exercise 1.4.1. (Go to Solution)

Write the key signatures asked for in Figure 1.30 and name the major keys that they represent.

Figure 1.30.

Solutions to Exercises

Enharmonic Spelling*

Enharmonic Notes

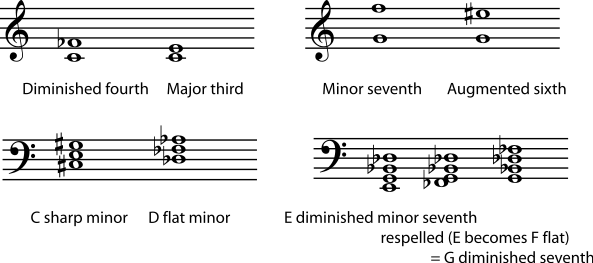

In common notation, any note can be sharp, flat, or natural. A sharp symbol raises the pitch (of a natural note) by one half step; a flat symbol lowers it by one half step.

Figure 1.32.

Why do we bother with these symbols? There are twelve pitches available within any octave. We could give each of those twelve pitches its own name (A, B, C, D, E, F, G, H, I, J, K, and L) and its own line or space on a staff. But that would actually be fairly inefficient, because most music is in a particular key. And music that is in a major or minor key will tend to use only seven of those twelve notes. So music is easier to read if it has only lines, spaces, and notes for the seven pitches it is (mostly) going to use, plus a way to write the occasional notes that are not in the key.

This is basically what common notation does. There are only seven note names (A, B, C, D, E, F, G), and each line or space on a staff will correspond with one of those note names. To get all twelve pitches using only the seven note names, we allow any of these notes to be sharp, flat, or natural. Look at the notes on a keyboard.

Because most of the natural notes are two half steps apart, there are plenty of pitches that you can only get by naming them with either a flat or a sharp (on the keyboard, the "black key" notes). For example, the note in between D natural and E natural can be named either D sharp or E flat. These two names look very different on the staff, but they are going to sound exactly the same, since you play both of them by pressing the same black key on the piano.

Figure 1.34.

This is an example of enharmonic spelling. Two notes are enharmonic if they sound the same on a piano but are named and written differently.

Exercise 1.5.1. (Go to Solution)

Name the other enharmonic notes that are listed above the black keys on the keyboard in Figure 1.33. Write them on a treble clef staff.

But these are not the only possible enharmonic notes. Any note can be flat or sharp, so you can have, for example, an E sharp. Looking at the keyboard and remembering that the definition of sharp is "one half step higher than natural", you can see that an E sharp must sound the same as an F natural. Why would you choose to call the note E sharp instead of F natural? Even though they sound the same, E sharp and F natural, as they are actually used in music, are different notes. (They may, in some circumstances, also sound different; see below.) Not only will they look different when written on a staff, but they will have different functions within a key and different relationships with the other notes of a piece of music. So a composer may very well prefer to write an E sharp, because that makes the note's place in the harmonies of a piece more clear to the performer. (Please see Triads, Beyond Triads, and Harmonic Analysis for more on how individual notes fit into chords and harmonic progressions.)

In fact, this need (to make each note's place in the harmony very clear) is so important that double sharps and double flats have been invented to help do it. A double sharp is two half steps (one whole step) higher than the natural note. A double flat is two half steps lower than the natural note. Double sharps and flats are fairly rare, and triple and quadruple flats even rarer, but all are allowed.

Figure 1.35.

Exercise 1.5.2. (Go to Solution)

Give at least one enharmonic spelling for the following notes. Try to give more than one. (Look at the keyboard again if you need to.)

-

E natural

-

B natural

-

C natural

-

G natural

-

A natural

Enharmonic Keys and Scales

Keys and scales can also be enharmonic. Major keys, for example, always follow the same pattern of half steps and whole steps. (See Major Keys and Scales. Minor keys also all follow the same pattern, different from the major scale pattern; see Minor Keys.) So whether you start a major scale on an E flat, or start it on a D sharp, you will be following the same pattern, playing the same piano keys as you go up the scale. But the notes of the two scales will have different names, the scales will look very different when written, and musicians may think of them as being different. For example, most instrumentalists would find it easier to play in E flat than in D sharp. In some cases, an E flat major scale may even sound slightly different from a D sharp major scale. (See below.)

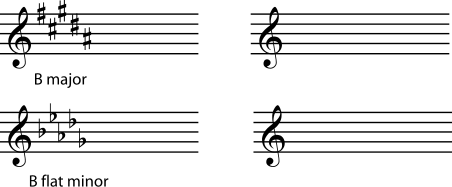

Figure 1.36.

Since the scales are the same, D sharp major and E flat major are also enharmonic keys. Again, their key signatures will look very different, but music in D sharp will not be any higher or lower than music in E flat.

Figure 1.37. Enharmonic Keys

Exercise 1.5.3. (Go to Solution)

Give an enharmonic name and key signature for the keys given in Figure 1.38. (If you are not well-versed in key signatures yet, pick the easiest enharmonic spelling for the key name, and the easiest enharmonic spelling for every note in the key signature. Writing out the scales may help, too.)

Figure 1.38.

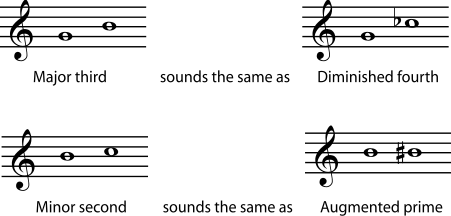

Enharmonic Intervals and Chords

Figure 1.39.

Chords and intervals also can have enharmonic spellings. Again, it is important to name a chord or interval as it has been spelled, in order to understand how it fits into the rest of the music. A C sharp major chord means something different in the key of D than a D flat major chord does. And an interval of a diminished fourth means something different than an interval of a major third, even though they would be played using the same keys on a piano. (For practice naming intervals, see Interval. For practice naming chords, see Naming Triads and Beyond Triads. For an introduction to how chords function in a harmony, see Beginning Harmonic Analysis.)

Figure 1.40.

Enharmonic Spellings and Equal Temperament

All of the above discussion assumes that all notes are tuned in equal temperament. Equal temperament has become the "official" tuning system for Western music. It is easy to use in pianos and other instruments that are difficult to retune (organ, harp, and xylophone, to name just a few), precisely because enharmonic notes sound exactly the same. But voices and instruments that can fine-tune quickly (for example violins, clarinets, and trombones) often move away from equal temperament. They sometimes drift, consciously or unconsciously, towards just intonation, which is more closely based on the harmonic series. When this happens, enharmonically spelled notes, scales, intervals, and chords, may not only be theoretically different. They may also actually be slightly different pitches. The differences between, say, a D sharp and an E flat, when this happens, are very small, but may be large enough to be noticeable. Many Non-western music traditions also do not use equal temperament. Sharps and flats used to notate music in these traditions should not be assumed to mean a change in pitch equal to an equal-temperament half-step. For definitions and discussions of equal temperament, just intonation, and other tuning systems, please see Tuning Systems.

Solutions to Exercises

Solution to Exercise 1.5.1. (Return to Exercise)

-

C sharp and D flat

-

F sharp and G flat

-

G sharp and A flat

-

A sharp and B flat

Figure 1.41.

Solution to Exercise 1.5.2. (Return to Exercise)

-

F flat; D double sharp

-

C flat; A double sharp

-

B sharp; D double flat

-

F double sharp; A double flat

-

G double sharp; B double flat

Understanding Basic Music Theory is a comprehensive insight into the fundamental notions of music theory: music notation, rules of harmony, ear training, etc. It covers most of the topics needed to understand and develop your musical skills - with your favorite training tool EarMaster of course!

This fantastic mine of information was written by Catherine Schmidt-Jones et al. and originally published on OpenStax CNX.

Course Introduction

Although it is significantly expanded from "Introduction to Music Theory", this course still covers only the bare essentials of music theory. Music is a very large subject, and the advanced theory that students will want to pursue after mastering the basics will vary greatly. A trumpet player interested in jazz, a vocalist interested in early music, a pianist interested in classical composition, and a guitarist interested in world music, will all want to delve into very different facets of music theory; although, interestingly, if they all become very well-versed in their chosen fields, they will still end up very capable of understanding each other and cooperating in musical endeavors. The final section of this course does include a few challenges that are generally not considered "beginner level" musicianship, but are very useful in just about every field and genre of music.

The main purpose of the course, however, is to explore basic music theory so thoroughly that the interested student will then be able to easily pick up whatever further theory is wanted. Music history and the physics of sound are included to the extent that they shed light on music theory. Students who find the section on acoustics (The Physical Basis) uninteresting may skip it at first, but should then go back to it when they begin to want to understand why musical sounds work the way they do. Remember, the main premise of this course is that a better understanding of where the basics come from will lead to better and faster comprehension of more complex ideas.

It also helps to remember, however, that music theory is a bit like grammar. Languages are invented by the people who speak them, who tend to care more about what is easy and what makes sense than about following rules. Later, experts study the best speakers and writers in order to discover how they use language. These language theorists then make up rules that clarify grammar and spelling and point out the relationships between words. Those rules are only guidelines based on patterns discovered by the theoreticians, which is why there are usually plenty of "exceptions" to every rule. Attempts to develop a new language by first inventing the grammar and spelling never seem to result in a language that people find useful.

Music theory, too, always comes along after a group of composers and performers have already developed a musical tradition. Theoreticians then study the resulting music and discover good ways of explaining it to the audience and to other composers and performers. So sometimes the answer to "Why is it that way?" is simply "that's what is easiest for the performer", or "they borrowed that from an earlier music tradition".

In the case of music, however, the answers to some "why"s can be found in the basic physics of sound, so the pivotal section of this course is an overview of acoustics as it pertains to music. Students who are already familiar with notation and basic musical definitions can skip the first sections and begin with this introduction to the physical basis of music. Adults who have already had some music instruction should be able to work through this course with or without a teacher; simply use the opening sections to review any concepts that are unclear or half-forgotten. Young students and beginning musicians should go through it with a teacher, in either a classroom or lesson setting.

There is, even within the English-speaking world, quite a variety of music teaching traditions, which sometimes use different terms for the same concepts. The terms favored in this course are mostly those in common use in the U.S., but when more than one system of terms is widely used, the alternatives are mentioned.